The Future of Microscopy

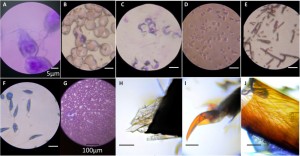

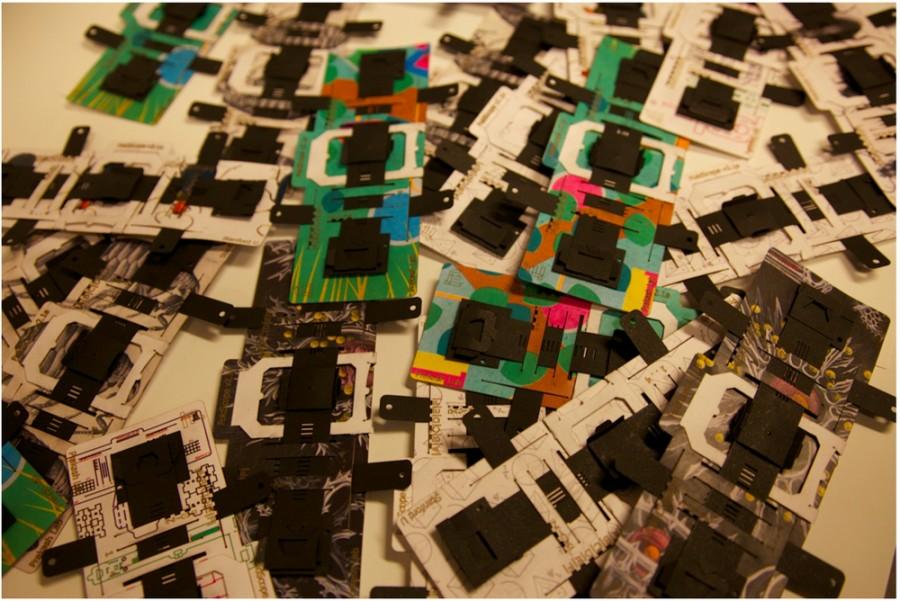

One of the largest problems the developing world currently faces is the proliferation of diseases such as malaria, and the need to treat and diagnose those who have been infected as a result. In Africa today, 1 million people die each year from malaria alone, with an additional 1 billion that need to be tested because they are at risk. As one might assume, African nations are not even close to the level of infrastructure needed to identify, diagnose, and treat these otherwise mitigatable epidemics. This is not so much the fault of African governments, but rather the fact that the main diagnostic tool for many of these infections–the microscope–hasn’t had any major design changes since 1940 in these countries. Microscopes are expensive to purchase, costly to maintain, bulky, and above all else, stationary; this is quite the opposite of what is needed to perform field diagnosis. Enter Foldscopes. Developed by Stanford Professor Manu Prakash, Foldscopes are origami-folded paper microscopes that cost a mere $0.50 a pop. Waterproof, smash-resistant, and affordable, these 70 x 20 x 2 mm3 slips of magic can magnify stains up to 2,000x with a sub-micron (800nm) resolution. They’re designed with scalability in mind, but more importantly, to accomplish a specific task.

Some are equipped, for example, with fluorescent filters built specifically to diagnose malaria. Another is tailored for jaundice, but regardless of what a Foldscope is designed for, they each can project on to flat surfaces with no need for an external power source. By creating task-specific, affordable microscopes, PrakashLab has solved one of the largest problems plaguing the developing world, in a method that can be easily adjusted to combat specific issues. Each Foldscope is printed on a single sheet of A4 paper, using surface tension to create the achromatic lenses used to magnify stains. The paper has no instructions and no language, but is color-coded so even the illiterate can properly assemble any of the dozens of different configurations. Though the invention is in position to change the paradigm of microscopy, each Foldscope still utilizes the standard glass stains used in medical research– ensuring existing equipment will not have to be changed. Prakash stated that one of the principal goals when inventing Foldscopes was to make field diagnosis easier, but not change existing equipment that could be re-used. Glass microscopy stains have been the norm ever since the Royal Microscopical Society introduced them as a replacement for ivory sliders in Victorian England, so replacing them would entail coming up with a better alternative, re-training those who already know how to use glass slides, and would erase any chance of cross-compatibility between traditional microscopes and the new Foldscopes.

Even though the invention is currently in a “closed-beta” (you must be invited to participate, and invitations won’t be sent out until the next cycle of testing), many members of the previous beta-testing round have already begun to change communities with Foldscopes. One anonymous member of the “Foldscope Community” took roughly a dozen general configurations of the device to Nairobi, Kenya, and instructed children grades 5-8 in the Kangemi slums on how to use them. The man was kind enough to leave the devices with the schoolteachers, hoping that this introduction to microscopy would inspire and help educate these impoverished children. Others have taken to writing their own instructions on the assembly process for those who prefer reading the instructions or are colorblind; several translations, such as the assembly pdf in Bengali, have been submitted by community members and are now part of the official Foldscope organization where information and materials can be requested by anyone. The entire project has a website anyone can contribute to and a twitter to follow developments as they occur.

Currently, most of the news updates are just photos of stains looked at with the paper microscopes, but just last December, PrakashLab teamed up with India’s Department of Biotechnology to train 300+ new Foldscope users. According to their website, the team is trying to target “yet-unreached communities (including students, teachers, non-profit educators, and national park rangers.” The goal is to get more people talking about Foldscopes, and to begin distributing as many as possible in the developing world. Though they’re still far short of their goal of making origami microscopy a norm in 3rd world countries, this is definitely a research team worth keeping a close eye on.

Hi! You must be really bored if you're reading this, but here we go. My name is Sebastian Lloret and I'm a Senior at Air Academy this year. I speak English,...

Tali • Mar 2, 2016 at 10:02 am

Really interesting stuff. I’m glad people are using their thinking caps! Also, the video at the top is super professional looking. Nice!

Ryan Henley • Mar 2, 2016 at 9:57 am

Sounds like liberal propaganda to me. Really interesting stuff though.