Making a Murderer

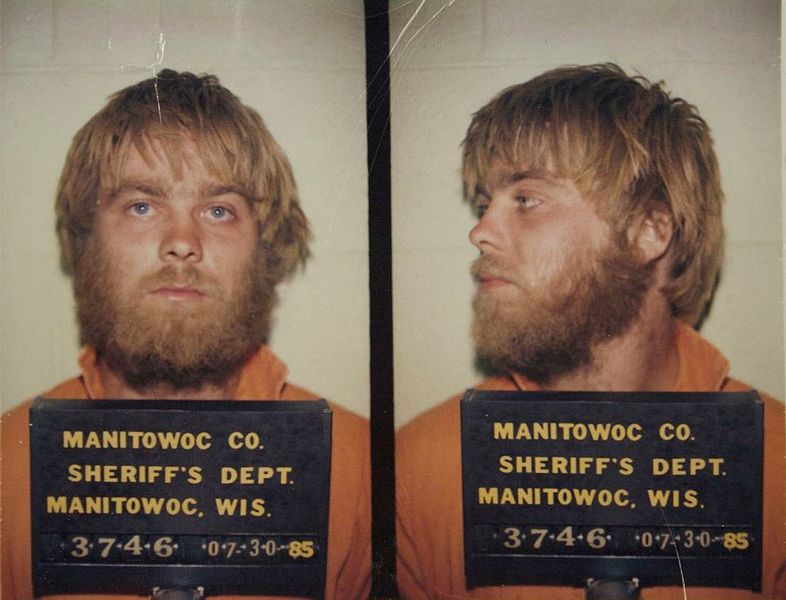

If anyone hasn’t already binge-watched Making a Murderer, then you’re not alone: the subject of the documentary himself, Steven Avery, is right alongside with you. Based on a true story, the Netflix Original Series follows the life of Steven Avery, a resident of Manitowoc County, Wisconsin, and the convicted party of an alleged murder. In 1985, Avery was arrested and convicted for the sexual assault of Penny Beerntsen, a woman who was brutally attacked while on a run in a Wisconsin state park and who identified Avery in a photo array and live lineup as the culprit. Aided by the Wisconsin Innocence Project, Avery was exonerated (absolved from any vindication) after further DNA testing of evidence was done and matched to someone else… but only after serving 18 out of 32 years in prison first. Despite having more than one alibi, his initial conviction was supported by prior altercations he’s had with the law including burglarizing a bar, pouring gasoline on his cat and throwing it into a fire, and assaulting and endangering the safety of his cousin; prior to ‘85, he had already served a total of 7 years and 7 months in jail/prison and 5 years on probation. However, Avery maintained his innocence on the murder of Beernstsen and was released from prison in 2003.

A $36 million federal lawsuit against Manitowoc County was filed by Avery; on October 31, 2015, the state legislature passed the Avery Bill, which “aimed to prevent wrongful convictions,” later renamed the “criminal justice reforms bill.” Yet, ironically, the bill wasn’t the only thing to pass that same day; that Halloween, a minivan for a sales ad in Auto Trader Magazine was set up to be photographed by Teresa Halbach for Avery. A few hours later, she mysteriously went missing. Just 12 days later, Avery was charged for her murder after her car and charred bone fragments were found at his family’s auto salvage yard. On June 1, 2007, Avery was formally sentenced to life in prison with no parole under murder charges as well as possessing an illegal firearm (but no charges of mutilation of the body). Since 2012, he has been held at the Waupun Correctional Institution in Waupun, Wisconsin.

Fast forwarding to today, Avery has recently filed for a new appeal citing violations of due process rights; Chicago-based attorney Kathleen Zellner has picked up representing Avery, as he was previously self-represented. Specifically, Making a Murderer (which has been being documented and put together for the past ten years), is intended to “explore issues and procedures in the Manitowoc County sheriff’s department that led to Avery’s original conviction, suggesting that the county officials had a conflict of interest in participating in the investigation of Halbach’s murder” as well as to “examine allegations of police and prosecutorial misconduct, evidence tampering and witness coercion.” The documentary gathers information through research and interviews of government officials, jury members, and even Avery himself. Following the popularity of the series, many petitions have also been sent to the White House to support Avery, such as one titled “Investigate and pardon the Averys in Wisconsin and punish the corrupt officials who railroaded these innocent men.” All claims have been denied from President Obama as he has no legal power to influence state cases.

Although Avery’s case is one to make the news, his situation is among 1,730 existing exonerations, according to the National Registry of Exonerations put together by the University of Michigan Law School. For example, Glenn Ford of Louisiana was sentenced to death row for 30 years for a murder he didn’t commit before being exonerated, as officials ignored acquitting evidence during trial. Michelle Murphy of Oklahoma was convicted of killing her 15-week-old-son in 1995; after blood work found at the crime scene didn’t match up with her own, she was exonerated after serving 20 years and having her daughter put up for adoption. Therefore, we seem to have a flaw in our criminal justice system.

The creators of the show, Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos, have stated that the show is not to endorse Avery’s case or help to clear his name, but to show the loopholes in the U.S. judicial system. Demos stated: “I guess it takes a lot to admit your mistakes, and I encourage people working in the justice system to have the humility to do that, if that’s how they feel. But I have not seen much of that happen. I think if you watch this series, I think it’s clear that the American criminal justice system has some serious problems, and it’s urgent that we address them. I don’t think anything in the series is unique to Manitowoc County or Wisconsin. I think this is an American story. We just chose this as a litmus test as one example, but it’s written large across our country.” Ricciardi expanded: “We’ve said this before, that this is a documentary. We’re documentary filmmakers. We’re not prosecutors. We’re not defense attorneys. We did not set out to convict or exonerate anyone. We set out to examine the criminal justice system and how it’s functioning today.”

So, especially for those second semester Seniors, as you Netflix and chill your days away instead of doing homework (or even coming to school), put Making a Murderer at the top of your list; you may learn a bit or two, and you definitely won’t be disappointed.

Hi I'm Natasha! I'm a senior at Air Academy and am excited to be on the Jetstream Journal staff for my first and last time. I like to hike and travel and...

Brady Becco • Feb 4, 2016 at 1:43 pm

Very interesting, I will have to check out the show!