Our English Curriculum is No Longer Relevant

For centuries, works of classical literature have been taught to students in English class. Students have pored over works by Shakespeare, Woolf, Orwell, Hemingway, and countless others. A glance at the required reading list for incoming freshmen shows texts such as The Lord of the Flies, Romeo and Juliet, and The Odyssey.

The Colorado Academic Standards do not explicitly reference classical works but allude to them. A Twelfth Grade Reading Standard states, “Read a wide range of literature (American and world literature) to understand important universal themes and the human experience.”

It begs the question: How much do these classical novels really teach students about the human experience?

According to sophomore Kianna Gray, very little at all: “Literature is meant to expand our world view and we can’t do that if we are stuck reading the same things four generations before us were reading,” said Gray.

English teacher Katie Klostermann disagreed. “Classical literature is classic for a reason,” said Klostermann. “While cool new stuff is being written all the time, it’s important to not abandon the works that influenced generations of people.”

It is indisputable that classical literature has served and continues to serve as a large focal point of the literature curriculum. English teacher Elise Hatfield said that it was difficult to calculate exactly how much of the English curriculum was comprised of classical works, but ball-parked it at about “half-and-half.”

Hatfield also acknowledged that classical literature is also a genre that’s difficult to define.

“You could put in terms of an author who’s written while [students] have been alive, or at least an author who’s been alive while you’ve also been alive,” said Hatfield.

Most students share a complicated relationship with classical literature. To many, it is a topic that feels antiquated, inapplicable, and out-of-touch.

“I don’t think we’ll use most of this. It would be a lot more helpful if we spent more time on distinguishing how to tell if news is legitimate or understanding legal writings as opposed to analyzing classical literature,” said Gray.

However, it can also be argued that classical works are not necessarily meant to be applied in real-world situations. Rather, classical literature serves as an important cultural aspect that students need to be familiar with.

“A lot of it has to with culture, so it doesn’t necessarily mean that you’re going to be a better banker. It’s more like maybe you’re going to be better at making connections with people…It sort of becomes a language of inclusion and a language of exclusion,” said Hatfield.

Klostermann also argued that classical literature serves as an important bridge between the past and the present.

“Classic literature connects us to each other and to the past,” said Klostermann.

Other students don’t negate the importance of classical literature but believe it is greatly overemphasized in today’s curriculum.

“It’s really important cause it helps give context to what we are reading today and is good for annotating purposes, but I also think that there are other things in English that we could focus on,” said sophomore Rachel Newton.

In addition, many students, including myself, feel that there is not enough diversity and representation within the literature taught. As an Asian-American female, there have been few, if any, times when I’ve strongly identified with any of the characters in a classical work of literature.

“Why don’t schools teach us about famous works done by women, or basically anyone else besides old white dudes?” sophomore Chloe Riggs asked bluntly.

Rarely are students assigned stories that are told from the perspective of a minority, much less written by someone who themself is a minority. Largely, the works students are exposed to in class represent one homogenous voice.

“I’m in tenth grade and not once have I read a book in class about women’s rights, religious tolerance, the struggles of mental illness, or anything about ableism in our society,” said Gray.

The only counterexample that comes to mind is To Kill A Mockingbird by Harper Lee, and even then, “many black people feel like that book support the white savior complex more than actually combating racism, so it isn’t a great text to reference,” said Riggs.

“After eight years of teaching, this is the first year that we’ve had a female author in the sophomore curriculum,” admitted Hatfield. “I’ve pushed for that — more diversity and different perspectives in the works we read.”

Within the English department, there is progress being made. This year, sophomore English students will be reading two texts written by women, a work written by a Nigerian man, and Martin Luther King Jr.’s letter from a Birmingham jail.

“We’re headed in a direction where it is going to be more diverse and more representative, in the best way possible,” added Hatfield.

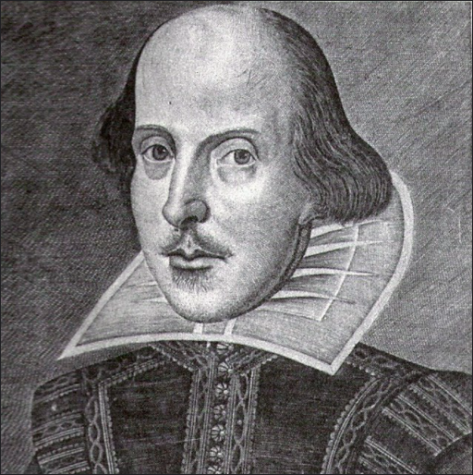

Arguably, one of the largest components of the classical curriculum is comprised of Shakespeare, which presents its own set of controversies among students.

Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be performed and to be witnessed on a large stage. Folger Shakespeare Library writes, “Pieces from Shakespeare — not to study as literature, but to read aloud because they were exemplars of good elocution, of good public speaking.”

Do Shakespeare’s plays have the same impact being read from textbooks in a classroom?

It is clear that while Shakespeare’s impact isn’t negligible, it has most certainly been diminished in the eyes of students, whether because of the way it is taught in school, or due to the few hundred years that have passed since Shakespeare’s works were published.

“Shakespeare was a fantastic writer but his works are overrated, especially in today’s schools,” said Riggs.

“It’s not as relevant because it’s so outdated,” said sophomore Jamie Cazier.

Most students don’t feel the need to erase classical literature from the English curriculum entirely, but most would prefer to focus less on Shakespeare and more on other, real-world applicable topics, such as grammar or vocabulary.

“I think that Shakespeare has some good lessons that still apply today, but we may focus on it a little more than needed,” added sophomore Kya Shatzer.

“Despite the praise I just [gave], I do have mixed feelings about only teaching the classics. So, while I think teaching the classics is important, I also recognize it’s not what most teenagers are interested in and maybe we could mix it up a bit,” said Klostermann.

Interestingly enough, that was exactly how Shakespeare first introduced to schools. “This was a time…certainly Shakespeare was not part of the curriculum,” reads Folger Shakespeare Library.

Shakespeare was considered to be popular culture and was not taught in class until well into the nineteenth century (nearly 300 years after those works were published!) when it became apparent that students were interested in it. Only then was it introduced to the curriculum.

It is a pattern that appears to be repeating in the modern English curriculum. So, whether Shakespeare or any other classical literature for that matter, are relevant or not, it is clear that they will continue being taught in class for quite some time.

Perhaps, in a few hundred years, The Hunger Games or Harry Potter will become the new focal points of the classical English curriculum.

Hey all, I'm Elaine! I'm a junior, and I'm super excited to be in my second year with the Jetstream Journal. Additionally, I'm involved in speech and debate,...