Feminists Provide Food for Thought: The Journey of Women in Science

I wasn’t a feminist before I started taking high level math and science courses. Up until then, I had not felt like I needed feminism. After all, hadn’t I managed to do just fine without it? There was no single incident that changed my mind; it was more like a building gradient of frustrations.

It’s hard to describe the feeling of being the only girl in the class, the discomfort of suspecting your accomplishments are being dismissed on account of your gender, the nagging knowledge that society somehow expects less of you than of your male counterparts. It was like diving. The weight started out as a dull throb–barely noticeable. But, with every interruption, every snide remark, the pressure would build a little more. Before I knew it, I was drowning.

Once I began to experience this sensation consistently, my world-view became permanently warped. As someone who had always considered myself a dominant voice in the classroom, I found myself falling silent.

I was shocked to find sexism still lingering in this society that I had previously viewed as so modern. I thought biases against women in science were some obsolete relic of a distant past, like typewriters and the last model of the iPhone. And yet, I was shocked to discover that subtler shadows of these biases persisted in my very classes.

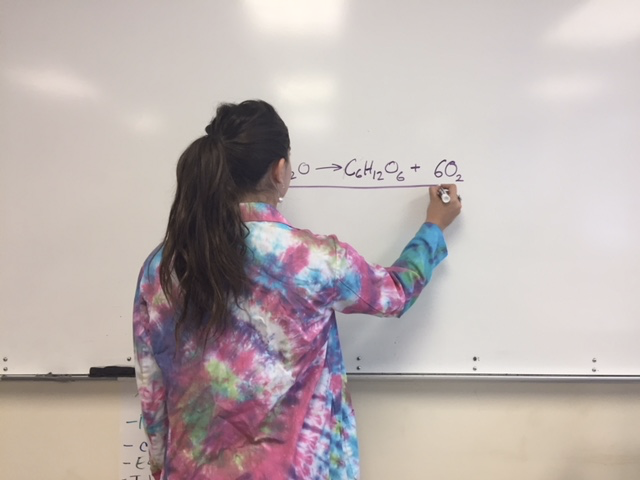

Senior Talia Markowski has taken a myriad of high level math and science courses including AP Biology, Honors Physics, AP Calculus BC, and, most recently, AP Chemistry. Markowski explained, “[In these classes] it’s definitely harder for me to share my opinions or my answers because there are definitely a lot more dominant voices.”

“Everyone is super competitive. They’re only worried about getting higher scores and stuff,” Markowski posited.

“A lot of guys are the ones like that.”

The fact that young women still struggle to feel comfortable in science class should not have surprised me as much as it did. Historically, it’s been a rough journey. For much of early history, women were confined to the private sphere. When they broke free into higher education they were expected to fill roles deemed “delicate and feminine.” Science was not considered one of those roles.

The first woman to graduate from medical school in America was Elizabeth Blackwell doing so in 1849 and the first black woman Mary Jane Patterson graduated 13 years later.

In 1861, Nettie Stevens studied mealworms to deduce the genetic basis of sex determination–a discovery that would be attributed to Thomas Hunt Morgan.

In 1922, Esther Lederberg discovered a bacteriophage and aided her husband in developing an improved technique for transferring bacteria between petri dishes. Her husband would share a Nobel Prize for this work with George Beadle and Edward Tatum.

In 1958, Rosalind Franklin used X-Ray diffraction to take an image of the structure of DNA that would later be used by Watson and Crick to posit its double helical structure. Watson and Crick won a Nobel Prize and Franklin’s work went unappreciated.

Now, I am certainly not trying to equate the modern experience of women in science to those in the past. Luckily, time’s arrow has soared swiftly forward, leaving some blatant sexism and discrimination behind it. But, it’s not what was left behind that concerns me, it’s what we carried with us.

Sincere portrayal of intelligent women is severely lacking in modern media; and when it does pop up, it’s often pandering. Barbie only recently discovered the microscope (surprisingly, it’s not pink) and TV women scientists are often reduced to love interests. We live in a world where women are still expected to sacrifice career to raise a family and continue to be a minority in careers in chemistry, physics, and engineering.

The 2017 update from the office of the Chief Economist noted that “women filled 47 percent of all U.S. jobs in 2015 but held only 24 percent of STEM jobs.”

Biology teacher Cris Robson attributed this potential continuing discrepancy to “gender roles that are assigned by society…without even realizing it,” especially to children and young adults. “Girls get dolls, boys get bug collecting stuff.”

Robson continued that this stage of youth is a critical time to instill the confidence young women and men need to succeed in the sciences. “[Being a scientist], It takes grit! Perhaps we need to teach more grit.”

While Markowski admits she does not “classify herself as a feminist,” she indicates that she is very aware of the detrimental gender stereotypes lingering in society. “[The stereotype is that] Guys are better at math. You hear those things everywhere.”

None of this is intended to villainize men for being confident and vocal in high-level STEM courses. But, perhaps there is something flawed with a system that breeds these highly competitive environments: environments where certain voices tend to disappear under the pressure and others tend to rise to the top.

Perhaps there is something flawed about a society where young women feel underestimated and must consistently call upon this “grit”–as Robson calls it–to prove themselves.

Science is about exploration. It’s about striving to understand and to feel more at home in the universe. It’s about the story of humanity and it is a narrative we must strive to make welcoming to all. Changing deeply ingrained societal beliefs is a long process. But, the first step is recognizing that a problem exists.

Hi! I'm Hillary; but, I go by Hill, Larry or anything in between. As a senior with a serious height deficiency, I won't take it too personally if you think...

Sasha Brunton • Oct 1, 2018 at 6:44 pm

I feel this, man. It definitely started early on for me though, being the only girl in Science Matters after school in 4th and 5th grade – I absolutely hated it (despite loving the activities). However, anybody who thinks that you can’t kick every single person’s butt – or at least give them a run for their money because your class has quite a few smarticle particles – in any math or science class is dead wrong.