Sleepless in S1

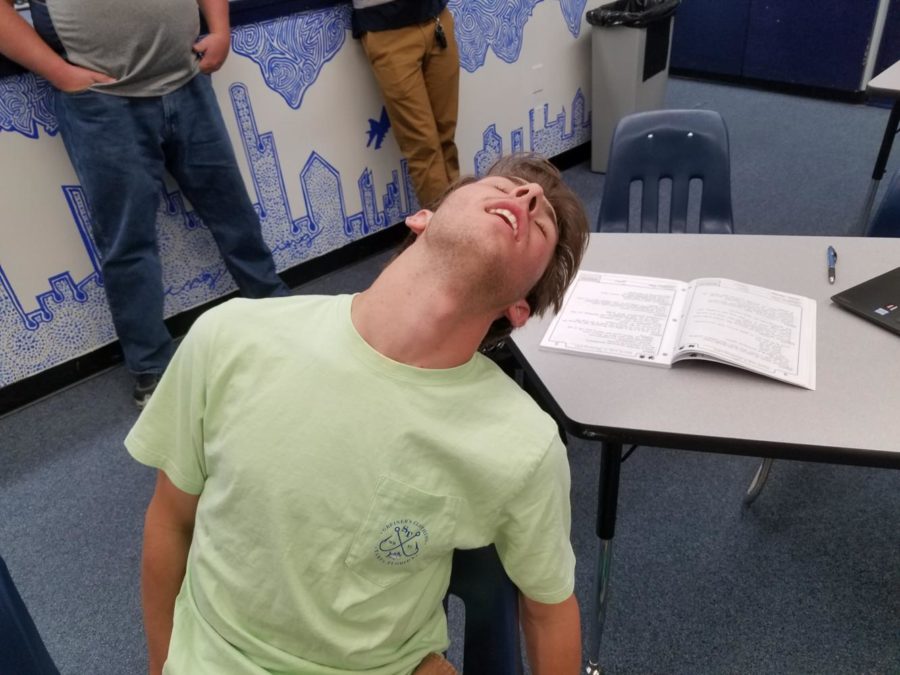

Senior Carter Rodny can’t help but take a snooze after a late night of doing homework. Original photo by Jonathan Flat.

October 14, 2017

Teens across the nation are not getting enough sleep. According to a poll by the National Sleep Foundation, more than 87% of high school students in the United States get less than 8 hours of sleep a night. For high school students, these numbers come with no surprise. What may be surprising, however, is that the National Institute of Health suggests teens need 9 to 10 hours of sleep daily.

Students at Air Academy see the effect of this widespread sleep deprivation in their daily lives. Rachel Noel, a senior taking several AP and honors classes, tells how she has spent “many nights staying up late to do homework,” sometimes going to bed hours past midnight. The next morning, Rachel wakes up at 6:30 a.m. to make it to school on time and finds it “harder to focus on what’s being taught in class that day.”

“I see students fall asleep all the time. I actually saw one student fall asleep in my last class,” says JD Walton, a senior here at Air Academy. Overhearing my conversation with JD, freshman Jaden Elias admitted, “I fell asleep twice in science last period.” In general, the vast majority of students that I interviewed confessed to sleeping less than 8 hours a night and feeling drowsy the next day.

Insufficient sleep, declared a “public health problem” by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), can lead to myriad health issues in teenagers and adults alike. Research by the Stanford University School of Medicine concluded that students not getting enough sleep are increasingly likely to suffer from “an inability to concentrate, poor grades, drowsy-driving incidents, anxiety, depression, thoughts of suicide, and even suicide attempts.” The CDC also agrees with these findings, suggesting that lack of sleep is likely to lead to the development of one or several chronic illnesses later in life, including diabetes, heart disease, obesity, hypertension, and even cancer.

The question is not whether the problem of sleep deficiency exists, but rather what can be done to alleviate the epidemic and allow teenage students to be successful in school.

Adolescents naturally have a biologic tendency to go to sleep later than younger children, or even many adults. This habit of staying up late is disastrous when combined with the early times students must wake up for school. To combat this issue, the CDC has been urging schools across the United States to have later start times. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) issued a policy statement “urging middle and high schools to modify start times to no earlier than 8:30 a.m. or later to aid students in getting sufficient sleep to improve their overall health.”

Upon learning of this suggestion by the CDC and AAP, students at Air Academy seemed completely on board with the 8:30 a.m. proposal. Freshman Sammy Nassief reflects the sentiment of the student body, stating, “I think it would be nice to start later and be able to sleep in a little longer. I wouldn’t even mind if that means school would end a little later.” With the unyielding support of health organizations along with the reinforcement of student opinion, why have schools implementing these suggested later start times?

The answer, it seems, lies in the expectations of parents in the workforce. A working parent may prefer an earlier start time that allows them to help their student get ready for school before they must leave for work. If students leave later for school, then their parents may be unable to help them get ready or even get to school. Because of this, school districts and individual schools—the entities that are able to decide start times—are wary of such a change that will impact the parental workers. “Money makes the world go round,” so a decision that may impede the supply of adults in the general workforce will not be easy to pass in the capitalistic society that we inhabit.

However, not all hope is lost. In the past, some schools have adopted a later start time in order to promote teen health and alertness. For example, Mr. Buhler, who graduated from Air Academy and has taught engineering here for 17 years, notes that the start time has changed since his time in high school: “When I was here, school started at 7:10.”

Change is possible, even necessary for our health. Yet, it will require considerable effort and a strong voice from the students, teachers, parents, and health professionals to persuade the district to achieve such a change.