FCC v. Net Neutrality

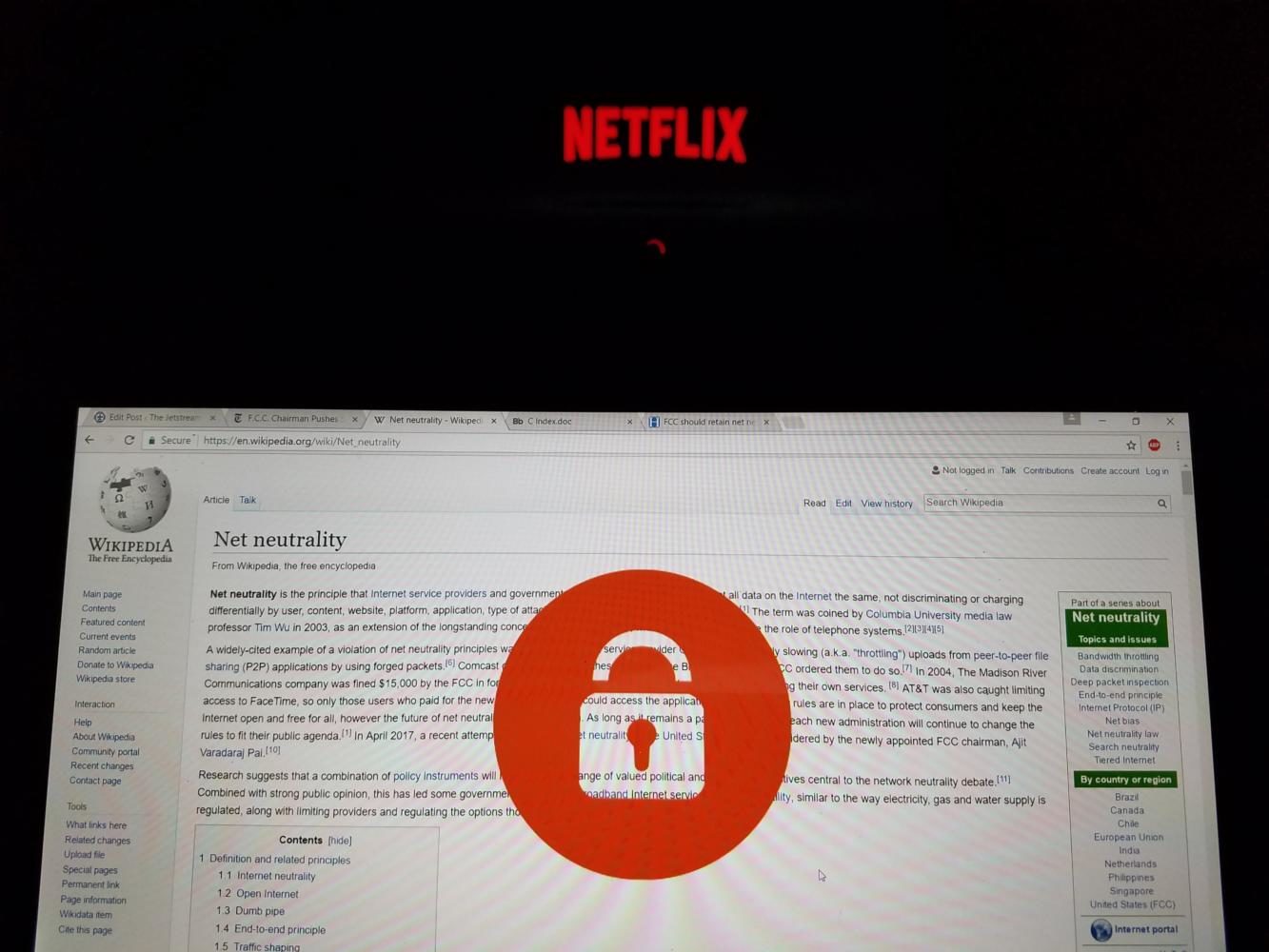

Imagine a world where the Internet is divided into pay-to-play fast lanes for internet and media corporations that can afford it and slow lanes for everyone else. In 2015, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) adopted rules for an “Open Internet” which aims to prevent this situation from happening by ensuring “consumers and businesses have access to a fast, fair, and open Internet” (fcc.gov). This concept, known as net neutrality, is being threatened by FCC Chairman Ajit Pai, who is currently pushing back on regulations that keep cable and broadcasting companies in check.

Since 2015, the FCC has emphasized 3 bright-line rules for an open Internet (as posted here):

- No Blocking: broadband providers may not block access to legal content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Throttling: broadband providers may not impair or degrade lawful Internet traffic on the basis of content, applications, services, or non-harmful devices.

- No Paid Prioritization: broadband providers may not favor some lawful Internet traffic over other lawful traffic in exchange for consideration of any kind—in other words, no “fast lanes.” This rule also bans ISPs from prioritizing content and services of their affiliates.

These rules are set in place to enforce the principle of net neutrality, and such enforcement has occurred in the past. In the case of Comcast Corp. v. FCC, Internet service provider Comcast was found to be in violation of net neutrality because of the deliberate throttling and blocking of uploads from peer-to-peer (P2P) file sharing applications. Comcast refused to stop blocking these types of websites such as Bit Torrent until the FCC ordered them to do so. The Open Internet rules establish a legal standard for other broadband provider practices to ensure that they do not unreasonably interfere with or disadvantage consumers’ access to the Internet. As consumers, you and I benefit from the fair practices regulated by the FCC.

These fair practices of net neutrality create a level playing field for companies that deliver information to consumers through the Internet. Also, the policy of Open Internet classifies broadband as a common carrier service, which are subject to firm federal oversight. This means that information travelling through the Internet reaches consumers without artificial delays imposed by telecom and cable companies. Artificial delays in the form of blocking, throttling, or paid prioritization are directly combated by the Open Internet policy of the FCC.

However, on Wednesday (April 26), Trump-appointed FCC chairman Ajit Pai outlined “a sweeping plan to loosen the government’s oversight of high-speed Internet providers, a rebuke of [the Open Internet policy] approved two years ago to ensure that all online content is treated the same by the companies that deliver broadband service to Americans” (The New York Times). Mr. Pai believes that the rules and regulations placed on cable and broadcasting companies are harmful to business. Yes, these regulations are not praised by big telecom companies like AT&T for the same reason that John D. Rockefeller disliked trust regulations: these rules protect consumers from the greed of corporations. If net neutrality loses to Pai’s FCC administration, the consumers and 99% of businesses that don’t sit at the top will be worse off.

Here is a brief example of why the top telecom and market companies favor the disappearance of net neutrality. In a world with no regulations pertaining to net neutrality, if Bing pays Comcast and Google does not, Comcast will ensure that Bing users receive their results faster than users of their competitor, Google. Comcast can do this in every corner of the Internet, from news to social media to P2P applications. The ISP reaps the profits while other companies and their consumers suffer from slower speeds or blocked websites. In essence, the loss of net neutrality means money for the most elite telecom companies and disadvantages for everyone else.

Mr. Pai says he is generally supportive of the idea of net neutrality but not of the rules that “went too far” and “were not necessary” for an open Internet, so this example is likely a bit exaggerated. Still, who knows how far a simple repeal of some regulations can go? Chairman Pai’s proposal is likely to pass because of a 2 to 1 Republican majority on the commission, so only time will tell if the Internet as we know it will stay fast, fair, and open.

Shalom le'kulam, my name is Jonathan Flat and I am the Managing Editor for this outstanding school newspaper. As a 16-year-old in the 12th grade, I'll...

Cole Pearne • May 2, 2017 at 12:19 pm

This is crazy! I didn’t even know this was an issue.

Carter Rodny • May 2, 2017 at 12:09 pm

I am dropping Comcast right now! X1 is a lie!

Robert Corl • May 2, 2017 at 11:52 am

This story is incredibly in depth and well done. I had no idea this issue was even a thing, and this editorial not only shed light on the issue, but explained it in a manner that most individuals can understand.

Jake Werner • May 2, 2017 at 11:47 am

Nice article! It is amazing how a few rules can change the way we use the internet.